100 Years of Progress

1879-1979

Northwestern Steel and Wire Company

The following is from the 100-year history of Northwestern Steel & Wire Company that was published in 1979. The Sterling Gazette reported that the article was written by Dan Dickinson, NSWS advertising manager and the research was conducted by Gunnar Benson and Harold Flory. Images are from the original publication.

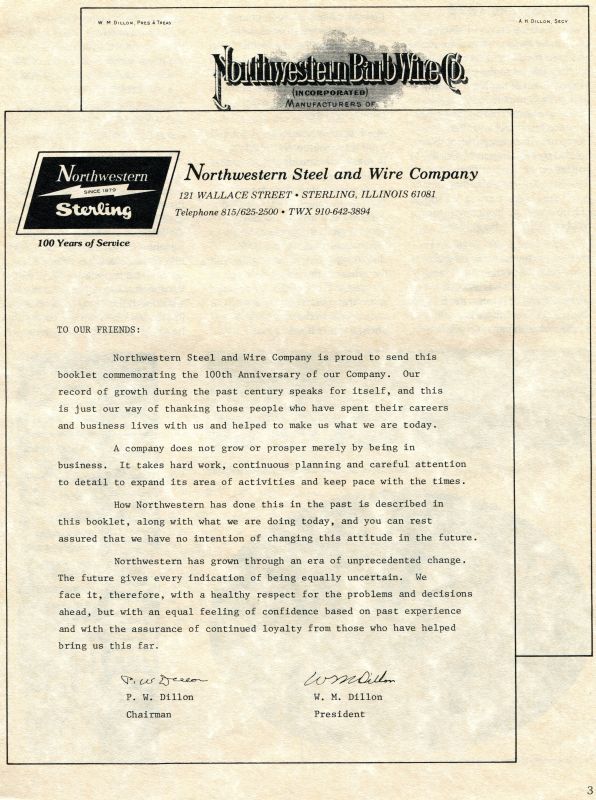

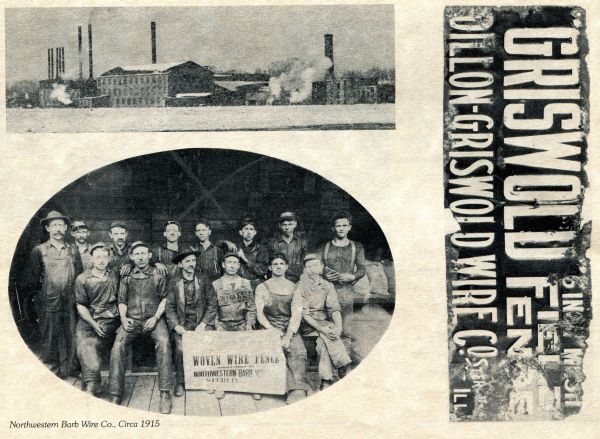

The year was 1879 It was a century ago… February 28, 1879 to be exact… that four young and industrious hardware merchants put their names to the papers of incorporation of the Northwestern Barb Wire Company and began writing the history of what is now Northwestern Steel and Wire Company. The incorporators were headed by Washington M. Dillon and his stepbrother, William C. Robinson, and they and their ten employees began turning out spools of barb wire in a single three-story building along the Rock River.

In 1979 Northwestern Steel and Wire Company is still headed by members of the Dillon family and the Company still has all of its facilities along that same Rock River… but now there are 4500 employees working in six plants that stretch for nearly three miles along the river. Barb wire is still produced, but the product line also includes hot rolled structural and bar shapes, such as beams, channel and angle, as well as nails, farm and residential fencing and reinforcing fabric.

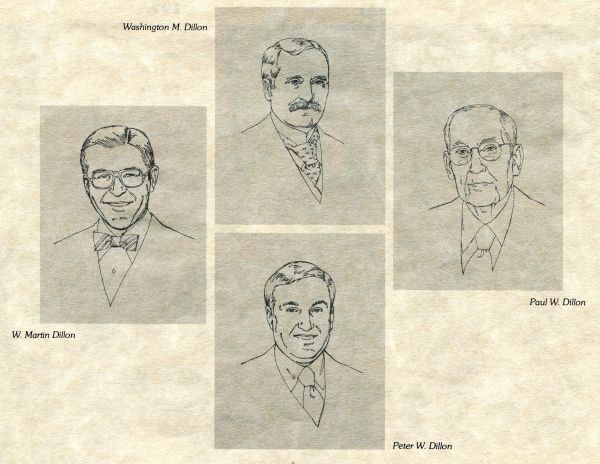

Northwestern is not a giant company… it is the thirteenth largest domestic steel producer, according to the latest published statistics… nor is it a midget, with net sales approaching $400,000,000 annually. But from its modest beginnings to the present, Northwestern has grown by the simple expedient of “doing the things the others didn’t do” and doing them well. The Company’s history spans the years from the era of waterpower to the age of nuclear energy, just as it spans four generations of ownership and management by the Dillon family: Washington – the founder; Paul the present board chairman; Martin -the current president; and Peter -a vice-president.

The history of Northwestern Steel and Wire is a story of free enterprise that yearns to be told …

The Early Years

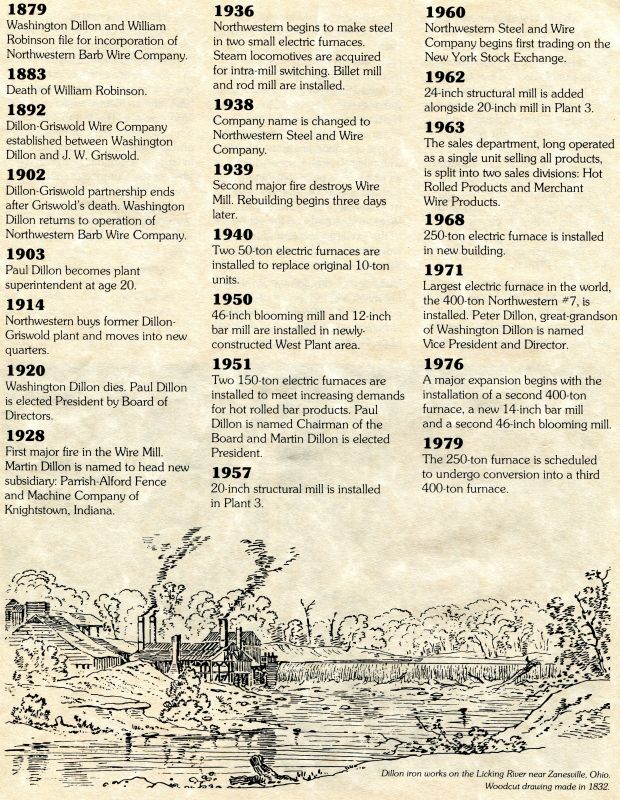

Washington Dillon’s roots were deep in the iron-working business; his grandfather, John, and great-grandfather, Moses Dillon, had built the first iron furnace west of the Allegheny Mountains at Dillon Falls, near Zanesville, Ohio. After the death of his father in 1847, young Washington eventually enlisted and served with the Army of the Potomac in the Civil War; after the conflict, he came west to St. Louis, then Page 4 moved on to Dixon, Illinois, and finally to Sterling, where he opened a hardware store in company with his stepbrother, William Robinson. Robinson also came by his interest in iron-working naturally: his father had been involved in the hardware and agricultural equipment business back in Ohio.

In the move that fostered today’s company, Dillon and Robinson banded together with two other local men to file for the incorporation of the Northwestern Barb Wire Company on February 28, 1879. The infant company was located on the Rock Falls side of the Rock River in a three-story building constructed of stone quarried from the river bed. The only product was the then-new barb wire, which had been invented in DeKalb, Illinois… about fifty miles east of Sterling and Rock Falls. They were taking dead aim on what amounted to a backyard market for the product the nearby farms of northwestern Illinois.

When the Company made its quiet entrance on the local scene in 1879, the announcement was nearly squeezed out of the news columns of the Sterling Gazette by the rising price of corn, which had reached the 25-cent mark at local elevators, and by reports of a rash of temperance meetings that directed a torrent of old Ned at “demon rum”. But 1879 was also the year in which the curious minds and restless hands that would lead America into its age of greatest progress were beginning to make their presence felt. It was the year in which Thomas Alva Edison would perfect his electric light in Menlo Park, New Jersey; when inter-city telephone communication would be demonstrated for the first time; and it was the year in which an Englishman named Dugald Clark would, for the first time, melt steel in a furnace that utilized an electric arc … a process that would be perfected to a high-degree of efficiency in our own organization nearly three-quarters of a century later.

At the outset, the Company purchased the smooth wire it needed from the American Steel and Wire Company in DeKalb, and ten employees were turning out 600 spools of barb wire a day. Power to run the barb wire machines came from a long-line shaft driven by water wheels installed on the river side of the mill race. In little Page 5 more than a year, local residents were taking notice of the Company’s progress: the newspaper reported that ten new barb wire machines had been installed and existing facilities had been improved as well.

Into the 20th century

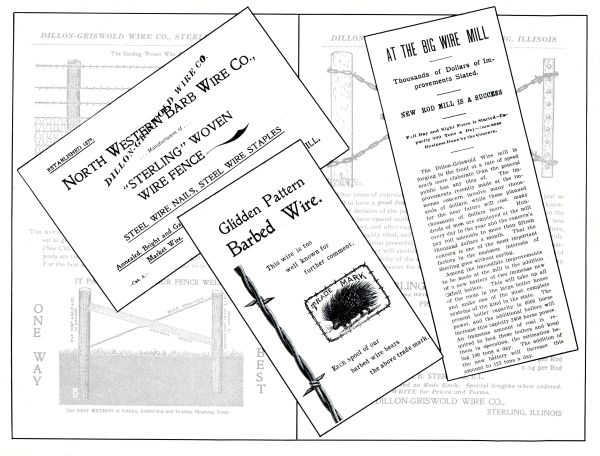

William Robinson’s tenure with the Company was brief: his death occurred in 1883, leaving Washington Dillon to continue the operation of the plant on his own. Nine years later, in 1892, he entered into a new partnership with J . W. Griswold and started the Dillon Griswold Wire Company in Sterling. Dillon kept his original plant across the river in Rock Falls, but devoted much of his time and energy to the new organization, which manufactured Dillon’s barb wire and Griswold’s bale ties, and later added field fence and nails to the product line. The new firm grew and prospered until Griswold’s death in 1902, when his heirs expressed little interest in managing the factory. Dillon dissolved the partnership shortly thereafter and returned to the operation of Northwestern Barb Wire Company.

When the Dillon-Griswold Company went into receivership in 1912, Northwestern purchased the remaining assets of the firm and the barb wire factory moved from Rock Falls into the Sterling plant’s newer and larger facilities. The elder Mr. Dillon was assisted in the move by his son, Paul W., who had been assuming additional responsibilities in the firm for the past few years. After Washington’s death in 1920, Paul–P.W. to his friends and associates–was elected president by the board of directors. He was an intense, capable young man whose leadership and enterprise quickly became apparent to those around him in the Company and in the community.

In 1928, the third generation of the Dillon family in Northwestern management, W. M. (Martin) Dillon, was named general manager of a newly acquired subsidiary firm: Parrish-Alford Fence and Machine Company of Knightstown, Indiana… Martin ran the firm for eight years at its Indiana location, and then supervised the moving of the facility back to Northwestern’s original home in Rock Falls, Illinois. Parrish-Alford continued to operate as a subsidiary until January of 1969, when it officially became Plant 4 of Northwestern Steel and Wire Company.

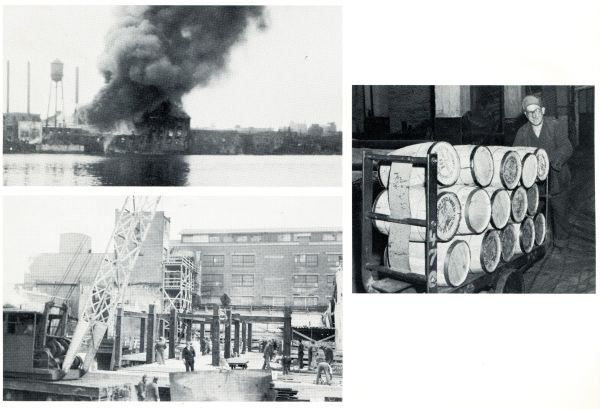

Before the decade of the 1920’s ended, the company suffered through its first disaster – a major fire swept through the wire mill, causing three fatalities and doing an estimated quarter-million dollars in damage. No time was lost in re-building; however, the fire had broken out on a Friday, but by the following Monday morning, the work force lending to the task of erecting a new and larger facility. It was an immense project for the company to undertake, but the next decade would present an even greater obstacle to overcome.

The Turning Point

Up until the 1900’s Northwestern was only a fabricator of wire products and had to depend on outside suppliers for the wire rods that were its raw material. During the hard times that followed the stock market crash of 1929, the company felt the economic pinch even more than the majority of the other steel companies. The firms that supplied rod to Northwestern were also competitors in the wire business. To get away from this potentially disastrous situation, Paul Dillon knew he had to begin melting steel making his own rods, but he was apparently blocked by a new piece of legislation called the National Recovery Act. In the midst of the depression, Congress had decided that there was an overabundance of steel production in the country and banned the installation of any additional facilities. The Act was later found unconstitutional, but at the time, it presented the greatest challenge ever to the survival of Northwestern Barb Wire Company.

Paul Dillon’s solution to the problem posed by the National Recovery Act was made obvious by an announcement on Mary 10, 1938, witch read:

“Consistent with the growth of the Company and the expansion of the manufacturing facilities… the shareholders of Northwestern Barb Wire Company have approved and now announce a change in the Company name to Northwestern Steel and Wire Company.”

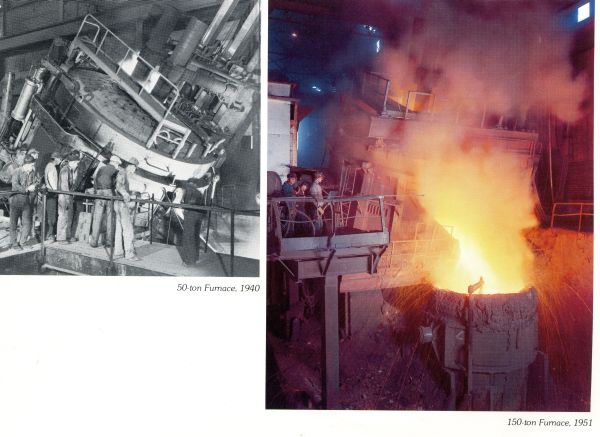

The answer had come in the wording of the NRA’s section on steel, which prohibited “the construction of blast furnace,” open hearth of Besserner steel capacity,” but neglected to mention electric furnace steelmaking. Although it had been used only for small quantities of specialty steels, the electric furnace offered Northwestern the chance to get into steelmaking.

Working closely with William Moore of Lectromelt Corporation, a pioneer in electric furnace steelmaking, and with engineers from Westinghouse Corporation, who but the necessary electrical equipment, Paul Dillon drove Northwestern through the legal loophole in the N.RA and installed two small ten-ton electric furnaces at the Sterling plant, along with a billet mill and a rod mill. Ignoring the experts who said carbon steel could not be made profitably in electric furnaces, Northwestern became a steel producer as well as a wire mill, and continues to this day to be at the forefront of electric furnace technology.

The construction of the steel plant began in the winter of 1935, a horrible winter with record cold temperatures and heavy snowfalls. Ironworkers, millwrights, electricians and other skilled tradesmen had to be brought in from as far away as Pittsburgh. Then there was the problem of power: each of the two furnaces required as much power as was then being consumed in the whole of Northern Illinois. But Illinois Northern Utilities, the electric company at that time, was willing to bring in a special line to the plant.

Once the furnaces were installed, the buying of the basic raw material needed, steel scrap, became a key factor in the Company’s profit picture. This most important function has rested in the hands of one man almost from the beginning: J. W. (Jack) Bowman, another member of the Dillon family, who joined the firm in 1935 and is currently Executive Vice President.

Times of Growth, Change

Before the 1940’s finally rolled around, Northwestern had suffered through another major fire, a disastrous flood and the storms of upheaval and change that rolled over the country with the coming of the industrial union organization efforts. A three-week strike at the Sterling plant in July of 1936 was the first in a drive by John L. Lewis’ organization to unionize the American steel industry. Before it was settled on July 29th, there was one fatality and several other men were injured in clashes between sympathizers, loyal employees and deputies. The late 1930’s was also the period when Northwestern started using steam-driven locomotives for intra-mill switching, a practice that continues today. In the early days of this unusual railroad, one of the more accomplished engineers was none other than Paul Dillon, who had learned the trade as a teenager working on the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad in Colorado while seeking relief from bouts with hay fever.

By the time the German Army invaded Poland in 1939, Northwestern had nearly recovered from the financial struggles involved in the start-up of the new steel plant and was well into a time of continuing expansion, improved profits. Two fifty-ton furnaces were installed in the early 1940’s to replace the original small furnaces and, like the rest of the country; Northwestern was operating at full capacity to assist the war effort.

In the early 1950’s, the Company embarked on yet another major expansion, the building of a complete new plant just west of the original facility to house two new 150-ton electric furnaces, a new 46-inch blooming mill and a 12-inch merchant bar mill. However, the new peacetime economy was not without its unique problems: a shortage of building materials plagued the housing industry, and the problem was complicated by the fact that the new steel plant was constructed on the site of a housing development that the Com an had large number of workers and their families, primarily Mexican-Americans who had come from the southwest to work at Northwestern. New housing programs were started by the Company which resulted in the construction of over 500 homes, with financing available through a payroll-deduction plan.

Back on the steel-production front, large-scale expansion was fast becoming the Company’s order of the day. The value of the physical plant grew by nearly $100 million in the period between 1955 and 1971. A complete 20-inch structural and plate mill was installed in 1957, and in 1962, a 24-inch structural mill was added alongside. There was no complacency in the area of electric furnaces in this period, either; a 250 ton furnace began operation in 1968, concept of operation known as Ultra-High Power, which achieved substantial increases in furnace productivity, In 1971, the first heat of steel was tapped from furnace # 7, a 400-ton unit that remains the largest furnace of this type in the world, A second 400-ton furnace was part of another major expansion program started in the mid-1970’s which also included the installation of a second 46.inch blooming mill, a new 14-inch merchant bar mill, and facilities for the manufacture of steel fence posts.

For Northwestern’s centennial year of 1979, there are plans underway to convert the 250-ton furnace into a third 400-ton unit to complete the erection of a’ second building for the 14″ mill and to install additional equipment and machinery for the 14″ mill finishing end.

It’s doubtful that Washington Dillon could have envisioned what his little barb wire factory would grow to become. A visitor to Sterling- Rock Falls today would find a huge steelmaking complex covering over 600 acres along the river between the two towns, The buildings that house the furnaces, rolling mills and other facilities echo with the sounds of “The Mill,” as the Company is known locally, and they are comforting sounds to the people of the area, Northwestern is by far the largest employer in the community, with an annual payroll of over $96,000,000 in fiscal 1978.

The key to the Company’s success is the development of its furnace department where the largest electric furnace department in the world can supply 2.3 million tons of raw steel annually for the rolling mills and wire plants to turn into finished products.

The operation begins with steel scrap, sorted by grade and loaded into huge charging buckets which are used to transfer the scrap to the furnace. The furnaces themselves resemble giant tea kettles on rockers; their steel shells are lined with refractory brick to hold the molten steel that can reach temperatures of 3000°, The entire roof of a furnace, including the electrodes, swings to the side so that a charging bucket can fill the furnace with scrap, Then the roof swung back into place, the electrodes are lowered, and the power is turned on to begin the melting process. In an electric furnace, the scrap is melted by the heat generated when the current arcs from one electrode to the scrap and from the scrap to another electrode. As the process continues, temperature readings and samples are taken and analyzed to insure that the steel being made conforms to specifications. When the analysis is correct, the electrodes are withdrawn and the entire furnace tilts on its rockers to pour the liquid metal into a waiting ladle.

Teeming, the term used to describe the process of filling the ingot molds from the ladle, is the next critical phase of the steelmaking operation. Here, the teeming crew and the operator of the giant 500- ton crane that holds the filled ladle have to work as a close-knit unit to move the melted steel to the molds, filling each one carefully to minimize defects that could hinder later operations. Once the ingot has solidified, it is stripped from the mold and transferred to the 46-inch mill reheat furnaces, where it is brought back up to the proper temperature for rolling.

The 46-inch mills, commonly referred to as blooming mills, are required to reshape the 13-ton ingots produced in the furnace department into semi-finished forms that can be used in the Company’s five finishing mills. In this operation, the white-hot ingot is rolled back and forth between the big mill’s rolls until it is reduced to approximately 9″ x 9″ in cross section, then sheared into easily handled lengths. These semi-finished forms, called blooms, can be transferred to the 24-inch and 20-inch structural mills in Plant 3, or they might be further processed into billets for the 14 mill at Plant 5, 12-inch mill in Plant 2, and the 10-inch rod mill in Plant 1.

The four mills that provide Northwestern with structural and bar shapes all operate on the same basic principles, with the 24 and 20-inch mills producing beam channel and structural angles, while the 14 and 12-inchmills make small angles, flats, rounds and reinforcing bar. A reheat furnace brings the semi-finished steel back up to proper temperature before it is started down the roll line. On continuous mills like the four, the bloom or billet first enter the roughing stands, where the product’s initial shape is formed.

Then it passes through the intermediate stands to the finishing stands, emerging exactly as called for in the specifications. The finished structural or bar shape is then stamped with identification numbers, cooled, cut to length and bundled for shipment to customers throughout the United States.

The operation of the 10-inch mill is similar in many respects to that of the other mills, but the finished product is hot rolled rod in coils, which is used to make the wire products sold under the trade name “STERLING”. In the wire drawing process, a cleaned and coated coil of rod is placed on the drawing machine, where it is turned into wire by pulling it through a series of carbide dies until it is reduced to the proper gauge for fabrication into nails and fencing.

Northwestern’s original product, barb wire, is just one of the many types of fencing that the Company now makes, and although the product itself has changed very little in the past 100 years, today’s barb wire machines are considerably more sophisticated than those put into use by Washington Dillon in 1879. Two wires are fed into the front of the machine, with a third wire that forms the barbs fed into the side. Through a twisting action, the two line wires are stranded together, with the third wire wrapped around, cut and pointed to form the barbs. In a nearby department of the wire mill, other machines wrap line and stay wires together to form field fence, one of the Company’s largest selling wire products. Downstairs, the steady staccato of the nail machines attests to the fact that Northwestern is a major supplier of nails in both bulk and consumer packaging. Here the wire fed into the machines is straightened, and then the head and point are formed so quickly that the eye cannot follow the process.

Other departments in the wire mill turn out hardware cloth, netting and fence stays, as well as the non-fabricated products such as baling wire, electric fence wire and re-bar tie wire. In addition, Northwestern sells merchant quality wire in coils and on stems to other firms that manufacture the many everyday products made from steel wire.

Across the river in Rock Falls, Northwestern’s Plant 4 turns out a number of welded wire products, with the greatest volume coming out of the reinforcing fabric department. The most widely known group of products from Plant 4, however, would be the plastic-coated lawn and garden fencing: Color-Guard, Lawn Guard, Tot and Lot and Tot and Lot Jr. These popular products are all produced by welding the wire into the desired design and then coating them with green or white plastic by the electrostatic spray process. Other departments at the Rock Falls plant produce welded wire fabric in a variety of sizes and gauges, galvanized yard fence and feedlot fence panels. In addition, the Company makes its own fence posts in a new facility designated Plant 6.

To move its structural, bars and wire products to customers around the United States, Northwestern relies heavily on its leased truck fleet, several common carriers and the railroads … but to move raw materials and semi-finished steel between the plants, the Company has continued to use steam locomotives, just as it did back in the mid-1930’s when the electric furnaces were first installed. Today, Northwestern Steel and Wire Company is the last full-time steam freight operation left in the country, with oil-fired “iron horses” doing all of the intra-plant switching. The Company’s 16 locomotives all came from the old Grand Trunk and Western Railroad and the sound of their steam whistles and labored exhaust echoes day and night throughout the mill.

Buildings and equipment alone do not make a company successful… people do. And from those original ten employees to the present workforce, Northwestern’s people have helped the Company reach the ripe old age of one hundred. They have come and gone by the thousands, from custodial workers to top management. Some have spent only a short time, many have spent a lifetime with Northwestern. The fact that so large a number have stuck through thick and thin reflects the loyalty which in large measure has been responsible for the Company’s success. And it reflects the faith that these employees have had in the ownership and management of the Company by the Dillon family.