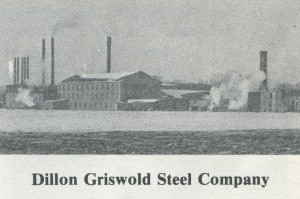

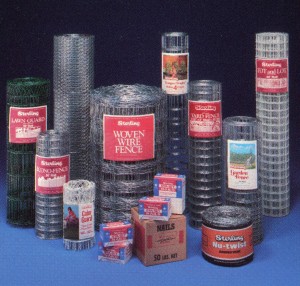

The following is a series of articles that ran in the Sterling Gazette in May – June of 1928 documenting a tragic fire in the Wire Mill. Three men died in this fire that, at the time, cost nearly half a million dollars.

May 19, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Three Live Lost in Fire

George Steltzer, John Burns and Frank Grate Are Missing

Death Rumors Were Denied Friday – Searchers Working In Ruin Today – All Employees Will Be Given Work by Company – To Rebuild At Once

Rumors that several men had lost their lives or wire unaccounted for in the disastrous file at the Northwestern Barb Wire company plant Friday morning were denied yesterday when a representative of the Daily Gazette south to ascertain the faces, but later in the day officials confirmed the report that three men, George Steltzer, 63 years, Frank Grate, 67 years, and John Burns, 70 years, were unaccounted for., following a thorough checkup.

The records fail to disclose any forth person missing, although there has been a rumor to the effect. The checkup again this morning, with no work of the missing men, confirms that believe that they perished. Owing to the intense heat in the debris it was impossible to make much of a perch late yesterday afternoon or night for the bodies but this morning a crew of men was engaged in the hunt.

The property loss was also larger than it was at first thought and is now figured at $400,000. All of the employees will be put to work by Monday morning and work on the erection of a new building will be started at once.

Old Employees Missing

Mr. Steltzer, one of the missing men, worked at the wire mill for a period of 22 years and then, after leaving the employment of the company, he returned last summer and had been working there since. He is survived in his immediate family by his wife and one daughter, Mrs. J R. Sides of Chicago.

Mr. Grate has been in the employment of the company for the past 37 years. He is survived by his wife and son Ed, of this city, and two daughters, Mrs. Stanly Hardy of Chicago and Mrs. Ed Meyer of Milledgeville.

Mr. Burns, the third employee who is missing, was a transient, He had been employed at the local mill at various times during the past 10 of 15 years and for the last year he had worked there continuously, Little is known regarding him.

Another employee was cut on the head by falling debris and was given attention at the Sterling Public hospital. His injury was not serious.

It is presumed that the men were overcome by the dense smoke and gas which quickly filled the plant and that they were unable to make their way to the exits. Their death has cast a pall of sorrow over their fellow workmen that is reflected throughout the entire community.

Work for all Employees

Contrary to the advance report that the mill would shut down and many men would be thrown out of work, officials stated this morning that every employee would be given work and that all should report to work Monday morning.

Work was resumed in the bale tie department last night and this morning 15 of the remaining fence machines were started up.

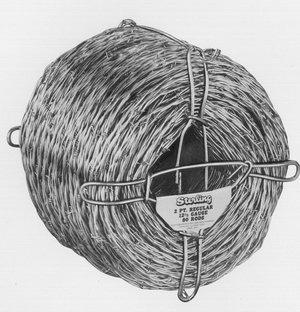

The barbed wire room began operations this morning and by Monday the 34 remaining continuous wire drawing machines will be ready for use.

Wire has been ordered from various other mills and some of it has already arrived. By the fore part of next week sufficient wire will be shipped in to keep everyone busy.

To Rebuild At Once

Paul Kornman, local contractor, has charged of the clearing the debris and it is expected that he will also receive the contract for the rebuilding of the portion of the plant destroyed. The new building will be of brick and fire proof construction, with basement, with is really the main floor, and two upper stories. It is understood, that the building can be ready for occupancy in from 60 to 90 days.

Lights are being strung throughout what remains of the old building in order that the work can go forward night and day in order to get everything cleaned up as quickly as possible and the bodies for the unfortunate victims recovered.

Further figures disclose that the lost will amount to around $400,000. The loss is covered by insurance. Orders for new machinery and parts have already been placed and full operations will be started just as possible. In the meantime all employees will be given work.

May 21, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Missing Men Not Found In Ruins Up To 1:30 today

Will Take Time to get Heavy Machinery and Rubbish Cleared Away

All of the employees of the Northwestern Barb Wire Company were put to work this morning. There is a large force at work both night and day in an endeavor to clean up the debris within the walls of the building which burned Friday morning.

Thus far a thorough search of the ruins has failed to disclose any of the remains of the three men, Frank Grate, George Steltzer, and John Burns, who are unaccounted for. The task of removing the debris, including heavy machinery and tangled masses of iron and wire, will require considerable time.

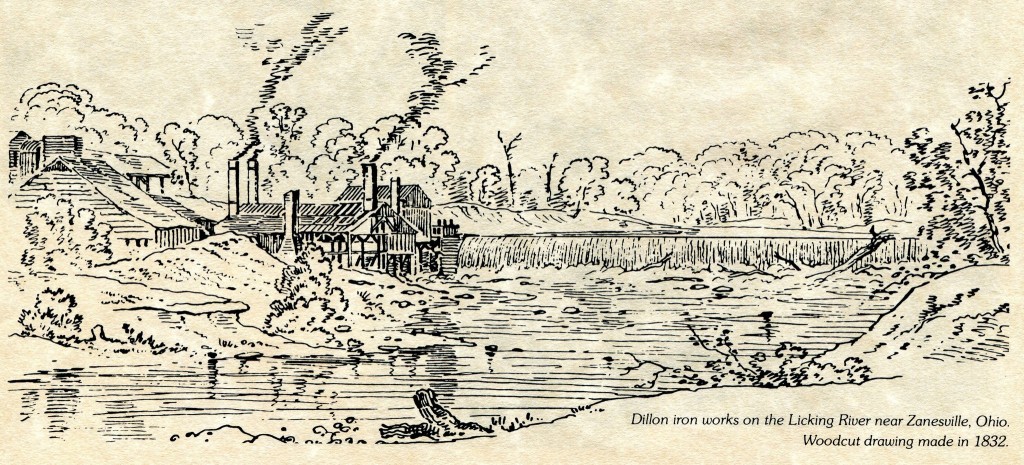

President Paul Dillon and Superintendent, Harry Hill is loud in their praise of the splendid work den by Chief Connie Nichols, his men and the volunteers. Mr. Dillon stated this morning that it was one of the best fire stops he had ever seen, and both he and Mr. Hill say the fire shows that Sterling has a real department.

May 22, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Charred Body Found In Mill This Afternoon

Could Not Be Identified At First Glance – Search For Other Two

The body of one of the men burned in the wire mill fire of Friday night was found by workers removing the debris of the fire about 2 o’clock this afternoon. At first examination the body could not be identified by the workers, but a more thorough examination is being made and possibly clothing, trinkets or other means of identification will be found.

The body was found near the door about the middle of the north side of the drawing room in front of what are known as the “bakers.”

No trace of the bodies for the other two men believed to have perished in the fire has been found. Workmen are working in day and night shifts in clearing the debris, but it is all in such a tangled mass that it will take a long time to get it all cleared up.

It is impossible to tell just where the bodies will be found as the men might have been overcome by the intense gaseous smoke and fumes as they ran for an exit or as they went for their clothes hanging in the coat room.

From the time the first call of fire was made it was but a matter of approximately a minute before the building was entirely filled with smoke and it was impossible to see one’s hand in front of them.

Mayor Burkholder last night at the city council meeting alluded to the low water pressure at the time of the fire, and Manager E. MacDonald of the Illinois Water Service Co., who was present, stated that an open six-inch pipe in the mill, which was not closed until after the fire, and another six-inch pipe which somebody was able to reach and shut off during the fire, caused the low pressure, as the new and old pumps at the pumping station were both going at high speed and ware pumping at nearly a 6,000,0000 gallon a day rate during the fire.

The one reservoir in use at the station held out to furnish the supply, but was beginning to run low. The valve permitting water to run back to the pumping station from the stand pop was not needed. Mr. MacDonald said that there was not means of increasing the pressure with a six-inch main running open at the point of supply for the pumpers.

May 23, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Charred Body of the Third Missing Man is Recovered

The bodies of all three of the employees of the Northwestern Bar Wire Mill, who lost their lives in the fire of last Friday morning., have been found, the third being uncovered in the debris about 1:15 o’clock Wednesday afternoon. With the first remains taken from the ruins indentified as Frank Grate, and the second body believed almost beyond doubt to be that of J. Burns, the last of the three to be recovered is the only other missing man – George Steltzer.

The last body was found in an elevator shaft, and while it is in better condition than either of the two previously found, there are no recognizable features. Workmen were engaged this afternoon in looking thought the debris near where the body was found in the hope that some article might be found that would lead to positive identification.

May 23, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Second Body is recovered from Wire Mill Ruins

Identify Remains of Frank Grate – Believe Other Is Body of John Burns

Two bodies have now been recovered from the ruins of the Northwestern Barb Wire company plant, where on last Friday morning fire caused a $400,000 property loss and claimed the lives of three employees. Frank Grate’s body was found yesterday afternoon and this morning a badly burned body was found about 15 feet east of where Mr. Grate’s remains were discovered.

The body found this morning, is believed to be that of John Burns, aged 70 years, a transient wire drawer. Beneath the right arm, which was tightly pressed across the chest, was found a strip of underclothing and also a fragment of a blue shirt. It was at first believed that it was the body of George Steltzer as he was wearing a blue shirt on that day. It was learned later, however, that Mr. Steltzer wore underwear with sleeves and the piece of underwear recovered was that of a full length sleeve. As only three persons are unaccounted for, the identification of the body recovered this morning and removed to the Melvin mortuary is doubtless that of John Burns. A portion of the arm of the body recovered this morning was very hairy while Mr. Steltzer’s arm was not.

Mr. Burns was an old timer and had worked in various mills about the country and had been employed at the local mill on several locations over a period of years. The last time he had worked here about a year and boarded at the Wire Mill Hotel. Very little is known regarding him. It is believed that he has a brother in the Pittsburgh district, but an effort to get in communication with him has been unsuccessful thus far.

The position of the body as it lay in the debris gave evidence that Mr. Burns was evidently endeavoring to make his ways thought the smoke to an exit, with was not far away. A search is being continued in the debris where the body lay for further identification.

First Body Found Tuesday

The first body found Tuesday afternoon was that of Frank Grate, 67, of this city. The remains were discovered near the north wall of the ruins, about 25 feet east of the west wall and a distance of about 10 feet from an exit, toward which he probably was wending his way when overcome by the dense gaseous smoke that nearly blinded and choked others, who narrowly escaped with their lives.

The remains were lying on some steel sheets of metal which covered the runways of the room and were not buried down in the ruins. With the removal of the body, a small piece of shirt wedged tightly beneath one arm in such a manner that the flames could not reach it, was recovered. This was taken to the home of Edwin Grate as part of the shirt which she had given her father-in-law for Christmas last year.

Coroner Swears In Jury

Coroner C.M. Frye took charge of the removal of the remains from the ruins and following identification they were removed to the Wheelock storage rooms in Rock Falls. The coroner’s jury consisting of H. F. Kidd, foreman, F. W. Scated, William Gaffey, L. A. Wheelock, Fred Compton and William Hayward, viewed the remains and were sworn in. Coroner Frye will not hold the inquest until the body of the third missing man is found.

With the finding of the remains of two of the three missing men, the workers continued their search with renewed efforts. Some are of the opinion, however, that the body of the one still unaccounted for is in the mill race, it being believed that he fell into the water in climbing hastily out of the window.

William Franklin Grate was born near Streator, Ill., November 10, 1863, the son of Sylvester and Eliza Grate. In 1899 he was married to Amanda Jane Havens, and shortly afterwards they moved from the old home in Table Grove, Ill., to this city, and with the exception of three years spent in the state of Iowa and one summer in Beardstown, Ill., they have resided here.

Mr. Grate first started to work in the Northwestern Barb Wire company plant in 1896 and had worked for the firm about 27 years.

The deceased is survived by his wife and three children, Edwin Grate of this city, Mrs. Stanley Hardy of Chicago and Mrs. Edward Meyer of Milledgeville.

The funeral will be conducted Thursday afternoon with a short service at the late home, on Fifth Avenue, at 3 o’clock and at the United Brethren church, of which he was a faithful member, at 2:30 o’clock. Burial will be in Riverside cemetery.

May 24, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Delay Inquest until Debris of Fire is Removed

Coroner wants to be Certain No More Bodies Are in Wire Mill Fire Ruins

The body of the last of the three unaccounted for workmen who lost their lives in the disastrous $400,000 fire at the Northwestern Barb Wire Company plant last Friday morning was removed Wednesday afternoon. The first charred body to be removed was that identified as Frank Grate, 67, and was removed Tuesday afternoon. Yesterday morning a body identified as that of John Burns, 70, was found, and about 2 o’clock in the afternoon the remains of George Steltzer were found.

Mr. Steltzer’s body was located covered with a great deal of debris in the elevator pit. It was the most difficult of the three to get to and remove. The elevator shaft was right next to an exit and it is evident that Mr. Steltzer was overcome just as he was a step of two from safety.

The remains of Mr. Steltzer and Mr. Burns were removed to the Melvin mortuary, where they aware viewed by the same jury as vied the remains of Mr. Grate at the Wheelock undertaking parlor. The jury was sworn in by Coroner C. M. Frye but the inquest will not be held for at least a day or two until all of the debris has been cleaned up from the fire. No one else has been reported as missing, but Coroner Frye thought it best to wait a day or so in order to be certain that there are no more bodies buried in the debris.

By working day and night in cleaning up the debris and wreckage the work has moved along very rapidly and aside from some of the heavy machinery witch was operating in the basement of the building there is little left to clean up.

The fire was the most disastrous in the history of the city. The anxiety which preceded the finding and identifying of the remains of the three missing men has been a great burden on the families and it is a great relief now that positive identity has been made.

Little is known regarding John Burns. He was about 70 years of age and had worked at the mill on various occasions during the past several years. Burns was a transient wire drawer and had worked in practically all the big mills in this county. It was said he had a brother in the Pittsburgh distract but this far officials of the mill have been unable to get into communication with any relative or near friend. It is possible that the remains will be buried in a local cemetery.

The funeral for George Steltzer will be held at the family home, on Johnson Avenue, at 2 o’clock, Friday afternoon. Dr. E. C. Harris of the St. John’s Lutheran church will be in charge of the rites. Burial will be in Riverside cemetery.

May 26, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Begin Building Wire Mill Plant

Preliminary work on the reconstruction of the burned portion of the Northwestern Barb Wire Co. mill has been started and will be carried on concurrently with the removal of the debris of the fire.

The new building will be of approved mill construction and will add considerable floor space to the factory, permitting an increase in the capacity of the plant. Definite detail of the plans will not be ready for announcement for several weeks.

May 28, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Section of Warehouse at Wire Mill Falls

Overload Causes Top Floor to Give Way – Part of Wall Pushed Out

Following closely on the heels of the damaging fire of 10 days ago, which caused a loss of more than $400,000 at the Northwestern Barb Wire Mill, came another disaster Sunday evening when a portion of the top floor of the new three story warehouse gave way, carrying several tons of wire crashing through the second and first floors to the basement, and also pushed out a portion of the south wall of the building. The accident occurred about 6 o’clock last night and was due to an overload being piled on the top floor, much of the material being a finished product which had been placed there following the fire.

It is considered fortunate that the accident occurred on Sunday. Had it happened on a working day, it might have coast several lives.

Although the reconstruction cost will be considerable, the financial loss is small compared to the loss of the much needed floor space and of the time that will be required in the making of the repairs. Since the recent fire it has been necessary to use every bit of available space. In the effort to clean up the plant after the fire, the materials have been piled wherever space could be found. The load was too heavy on a portion of the top floor and it gave way.

A railroad car on the switch track just south of the building was damaged some by the falling brick. The sprinkler system was damaged and the basement was filled with several feet of water before it could be shut off. The broken ends were plugged this morning and the system is again in order.

Under normal conditions the accident would not amount to a great deal, but coming s it does on top of the fire it makes maters more complicated and produces a larger handicap. Nevertheless the officers of the company are making the best of it and are rushing work toward the building of the new plant to replace the one destroyed by fire and will soon have the present difficulty adjusted.

May 31, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Inquest over Mill Victims Tonight

This evening at 7 o’clock Dr. C. M. Frye, coroner, will conduct the inquest at the Melvin mortuary to inquire into the deaths of Garage Steltzer, Frank Grate and John Burns, the three men who lost their lives in the recent fire at the Northwestern Barb Wire company plant.

The jury was sworn in at the time the bodies were recovered. The funerals and burials of all have occurred.

June 01, 1928 ~ Sterling Daily Gazette

Open Verdict in the Inquest over 3 Fire Victims

Evidence Heard by Coroner’s Jury on Wire Mill Fatalities Last Evening

An open verdict was returned last evening in the inquest held by Coroner C. M. Frye at the Melvin mortuary, after hearing testimony relative to the deaths of George Steltzer, Frank Grate and John Burns, the three men who lost their lives in the fire at the Northwestern Barb Wire company plant on May 18th.

The verdict in each case was that the men came to their death; being burned in the fire witch destroyed building No. 6 of the Northwestern Barb Wire Company, where they were employed, May 18th, 1928.

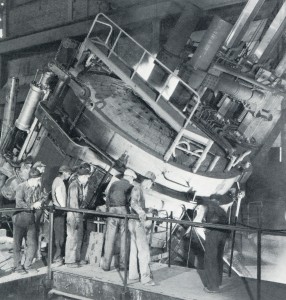

Evidence given the jury was practically the same as has been carried in previous reports of the fire, Simon Chapman stated that Chapman Bros., were removing some engines and had Robert Mayberry and Charles Morris doing the work. Mayberry told of using an acetylene torch and how the molten iron falling into some grease and oil started the fire. Morris, his helper, unbeknown to him had gone to get a drink of water. Morris was supposed to keep a fire extinguisher handy and put out any fires which might start. Mayberry said he grabbed several extinguishers but they were empty and that he got a hose but the water pressure was so low that the water barley came out the end of the hose. Within a minute the smoke was so dense and the fire so hot that Mayberry had to quit the room. When Morris got back he was unable to get into the room. Superintendent Harry Hill, Assistant Bert Bradley, T. J. O’Brian, employment manager, E. B. Van Horn, time keeper, and Sam Mitchell, steam fitter, testified. J. R. Sides of Chicago testified as to the identification of Mr. Steltzer and Edwin Grate told of the identification of his father, and Mr. Hill related how Mr. Burns was identified.

Paul Kornman, who had the contract of hunting for the bodies and cleaning up the debris, state that everything possible was down to speed up the work. By Monday following the fire he had 200 men working on the job. There were 150 tons of wire in addition to the machinery, fencing and debris to remove.