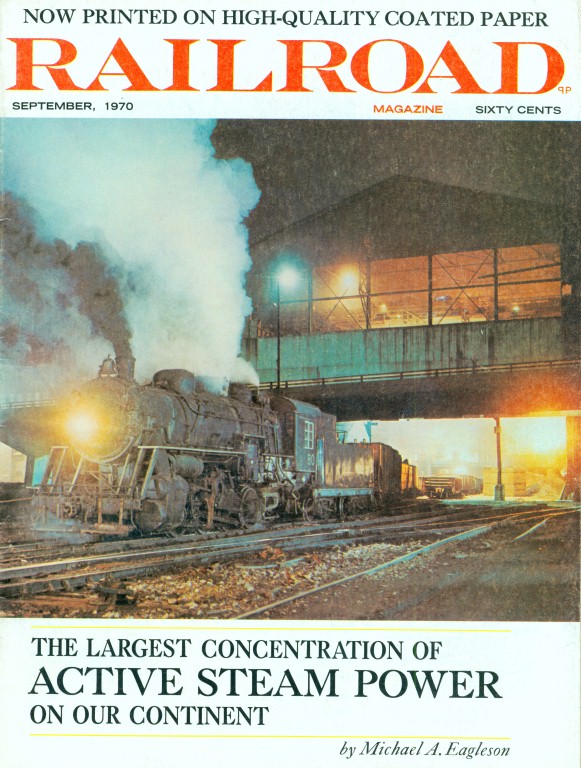

December 2011, I purchased a copy of RAILROAD Magazine off of eBay. The issue was from September, 1970. There was a neat article in it about Northwestern Steel & Wire and the use of the steam engines. Here is that text and some pictures of that article.

THE LARGEST CONCENTRATION OF ACTIVE STEAM POWER IN NORTH AMERICA

photos and text by Michael A. Eagleson

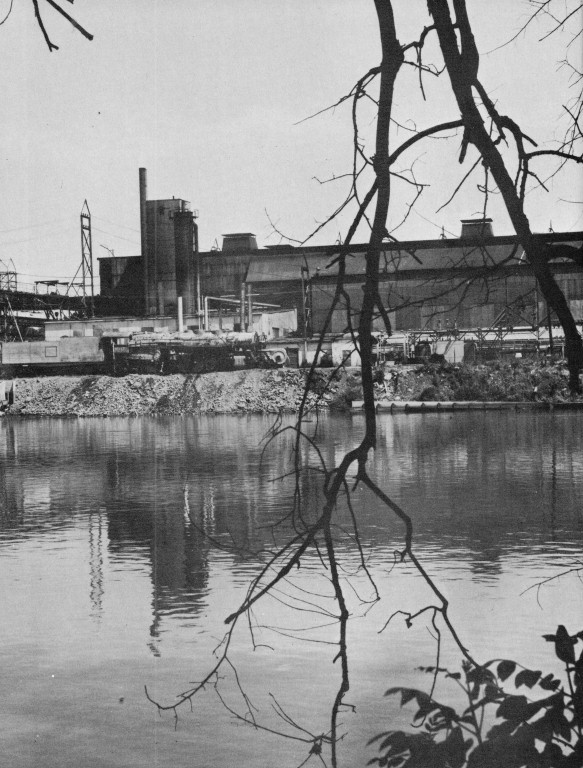

It was pouring rain as I stepped off a bus at the Dixie Hotel in Sterling, Illinois. After bouncing for an hour and a half through the night from Chicago, my thoughts were not on steam but on getting a room and some rest. This was the first of my five visits to the largest concentration of active steam power in North America today, and I wasn’t sure what I would find.

In the morning, I headed for the railroad yards at a fast walk, grumbling over the dreary wet weather. Once inside the visitors’ entrance to the Northwestern Steel & Wire Company, I was greeted with: “Oh, you’re another guy come to see our steam engines. Just wait here and we’ll fix you up.”

I sat down, listening to telephones ring and watching cute little mini-skirted secretaries on their way to the filing cabinets and the water cooler. At length a man handed me a release to read and sign, asking: “Where are you from, boy?”

“New Jersey,” I replied.

“We get ’em from all over. Last month we had a pair ‘from England. Damn if I know how they hear about us. You guys must be crazy to come so far just to see a bunch of dirty old steam engines.”

“Yes,” I said unconvincingly, anxious to get out of the office and on to the object of my own crazy thousand mile” plus journey.

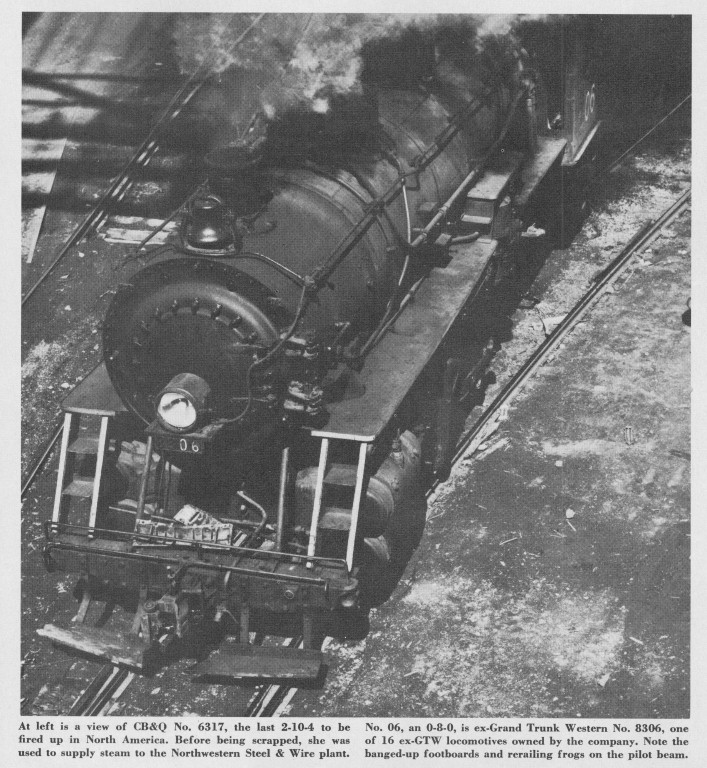

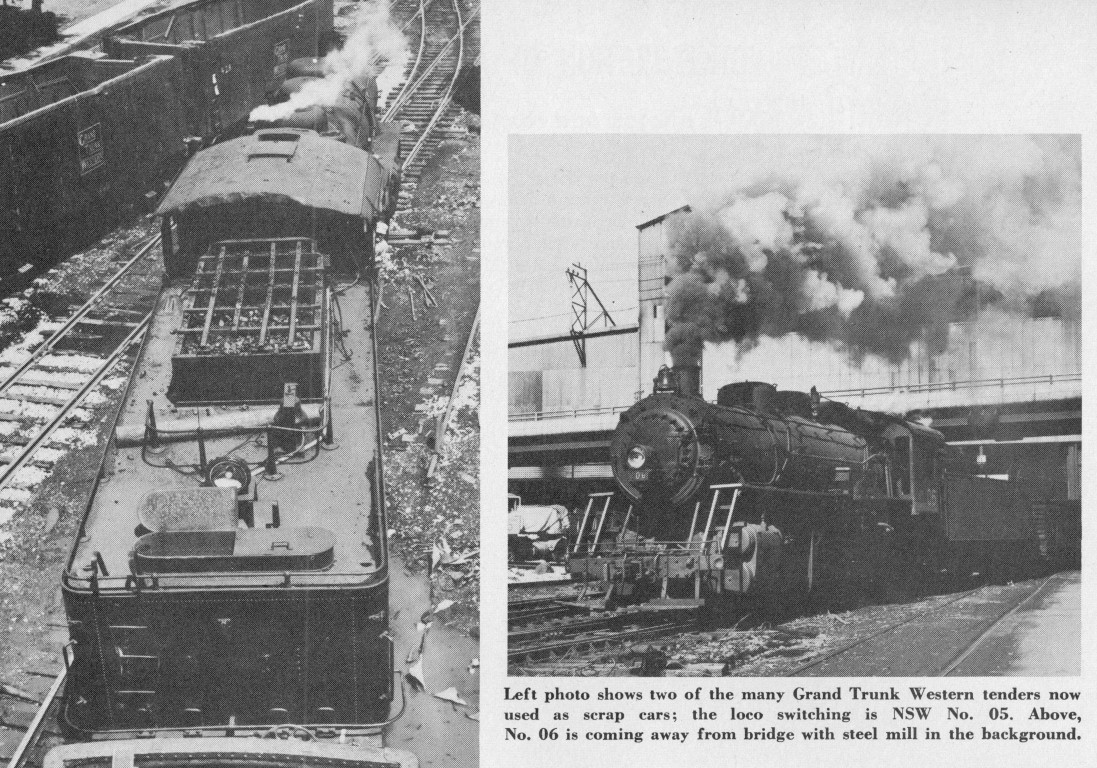

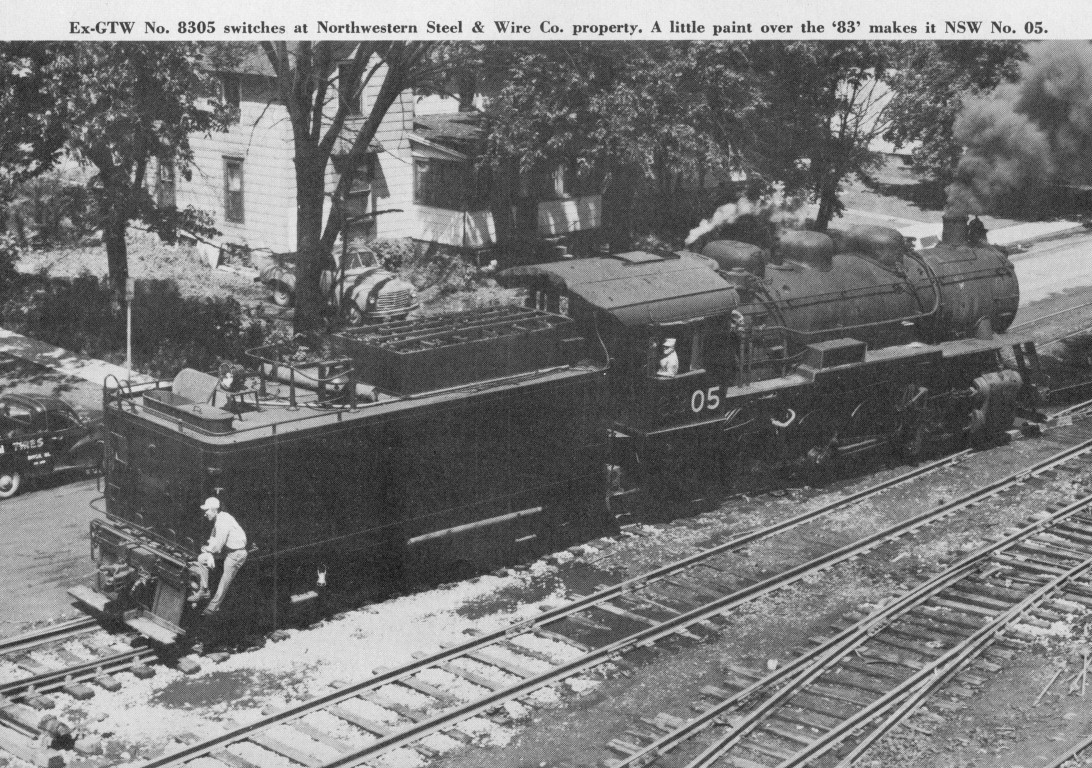

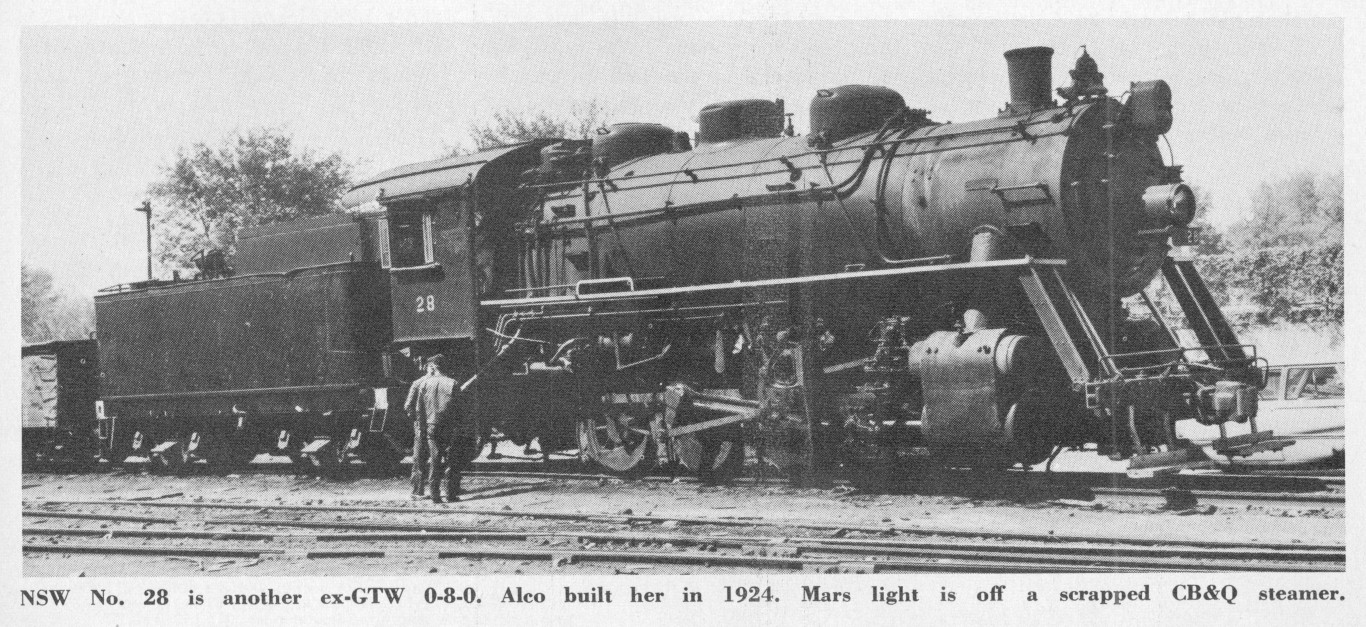

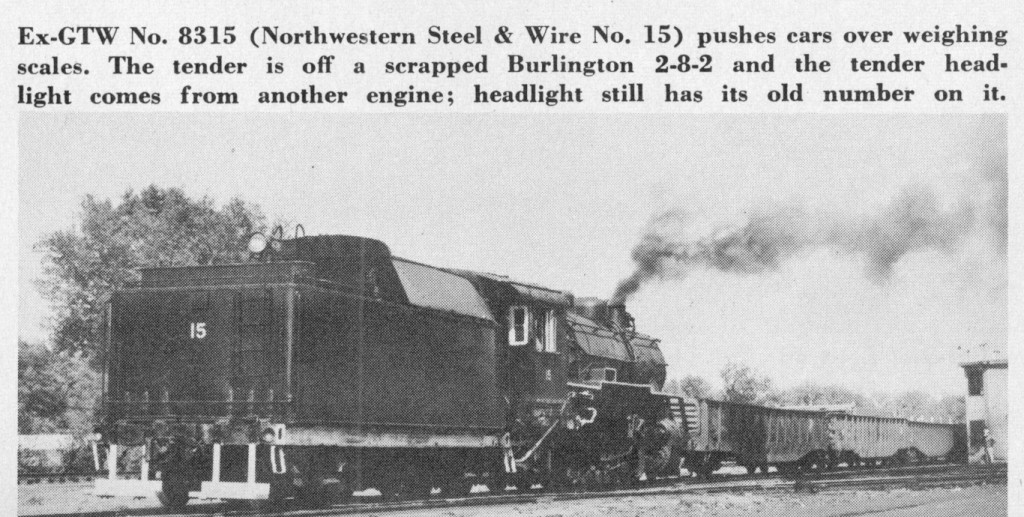

With a visitor’s pass visibly sticking out of my breast pocket, I walked over to the engine terminal. My eyes fell on six ex-Grand Trunk Western 0-8-0’s coupled dead in engine-to-tender fashion. Their parental heritage was obvious to a steam enthusiast; but there was something odd about the oscillating Mars lights from scrapped Burlington steamers, mounted above their headlights where the typically Grand Trunk Western V-shaped illumination boards used to be. Oh well, they’re steam, I thought, and moved on.

Just beyond, rose a square water tower, apparently made from a discarded engine tender, and beside it stood No. 05, another husky 0-8-0, but this one was alive. As I approached to examine the switcher more closely, she startled me by suddenly popping off. Almost simultaneously, an armed guard grabbed me, growling that I was on “company property.” I pointed to my visitor’s pass, but he shouted over the roar of the escaping steam: “You know, that’s only good for taking pictures on city streets. You can’t enter our property.”

Slinking away behind a crossing shanty with rotten and warped clapboards, I mused disconsolately over the excellent photo I almost had taken before this confrontation. No. 05 had quit popping off now and was being stoked. Her thick black smoke faded.

Slinking away behind a crossing shanty with rotten and warped clapboards, I mused disconsolately over the excellent photo I almost had taken before this confrontation. No. 05 had quit popping off now and was being stoked. Her thick black smoke faded.

Wandering down the street that paralleled the tracks, I spotted another hot engine. She was resting directly underneath a highway bridge that crossed Rock River, connecting Sterling with Rock Falls on the opposite bank. White vapor leaked profusely from every joint of the loco, which I knew that Alco had built in 1924. Climbing onto the bridge and assuming a sentry position, I waited in the drizzle for some action.

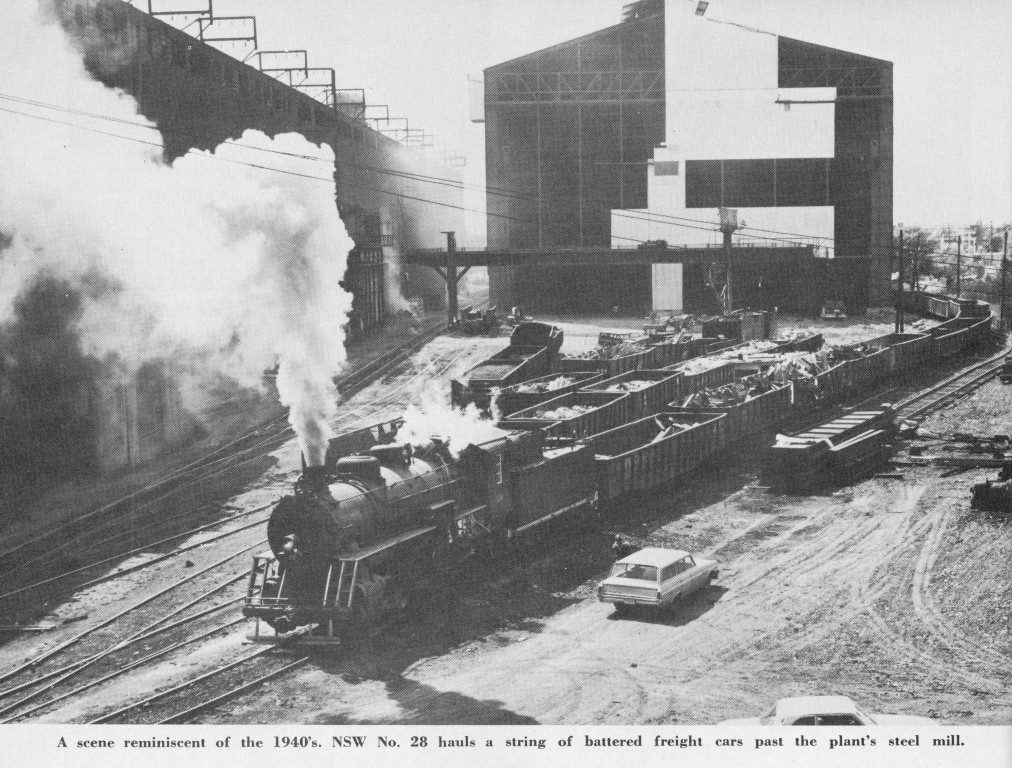

Ten minutes passed. Then I heard the first groan of the engine brakes releasing. The switcher slipped her 51-inch drivers on the wet rail while starting a long string of freight cars into the very heart of the steel plant. Her 45,175 pounds of tractive effort dug in. Her exhaust grew faster and louder, with the” echo reverberating from nearby buildings. She was in regular service. No fake Indian raids, Jesse James stickups, or kids and tourists looking at an oldtime steam train. This was the way things should be, and I was glad to be there. I enjoyed listening to the tones of her grime-covered brass bell. The old familiar bark of a big engine hard at work brought music to my ears. I was so enthralled that I scarcely noticed the beads of rain water spotting my camera lens or the hot cinders soiling my light tan jacket. This was why I had come to Sterling-to see and hear and remember.

No. 06, ex-Grand Trunk Western No. 8306, has kept working almost ten years after the brass collars had said she was obsolete and must go. How reassuring it is to see steam in regular service!

Northwestern Steel & Wire Company has a long history of being switched by steam. P. W. Dillon, the board chairman, grudgingly admits his affinity for steam locomotives. Mr. Dillion, now in his eighties, says they are good for at least another ten years, but I doubt it. Replacement parts are almost impossible to get today. Such items, as a rule, are either scavenged from the out-of service spare 0-8-0’s or made by NSW shopmen under the supervision of chief shop mechanic Larry Cain. He and his three assistants are responsible for keeping the herd of steamers running.

Even so, Dillon’s main argument at least to his board of directors-for keeping the steamers so long is purely economics. Yes, I said economics! Steam is accused of being expensive to operate, particularly in yard service where much time is spent in just sitting around. This is not true at Northwestern Steel & Wire.

“A diesel switcher, a new one, costs $180,000,” Mr. Dillon says. “We’ve got mountains of scrap iron around here, and, if the diesels brush against them the traction motors are likely to be damaged. And when one of them derails, there would be damages, too.”

Not so with steamers. They can bump into obstructions, or stub their toes and derail, but keep right on running with a minimum of repair. Evidence of this is seen in the mangled footboards on the plant’s engines. They are, you might say, battle scars.

Northwestern has always used steam, usually hand-me-down switchers. In the late 1940’s it had little ex-CB&Q 0-6-0’s. Next came 0-6-0’s from the Illinois Central and the Chicago & North Western, and finally ex-Burlington USRA types with the same wheel arrangement.

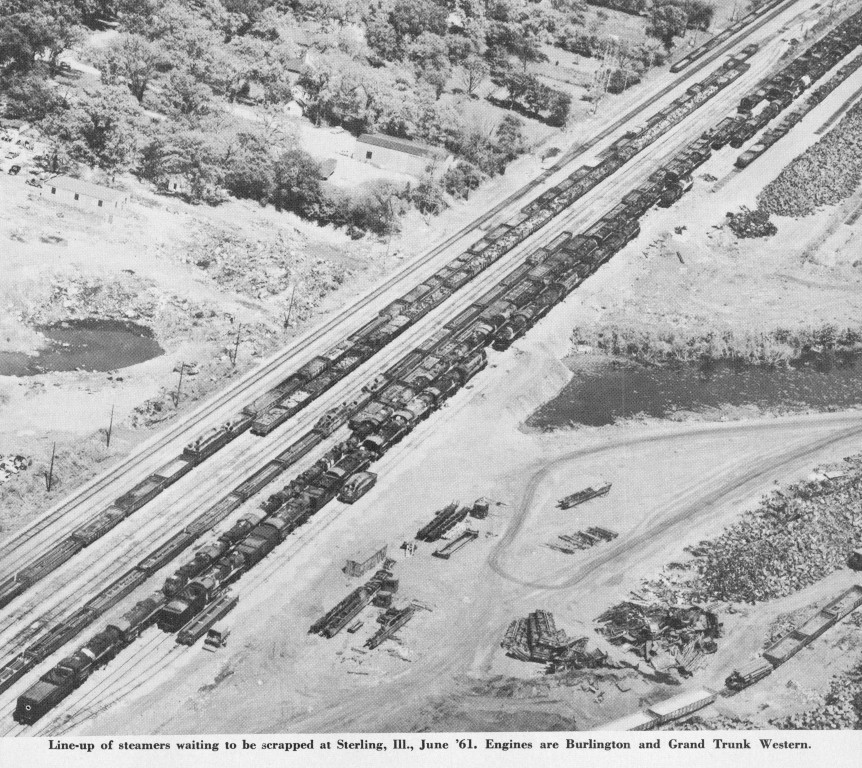

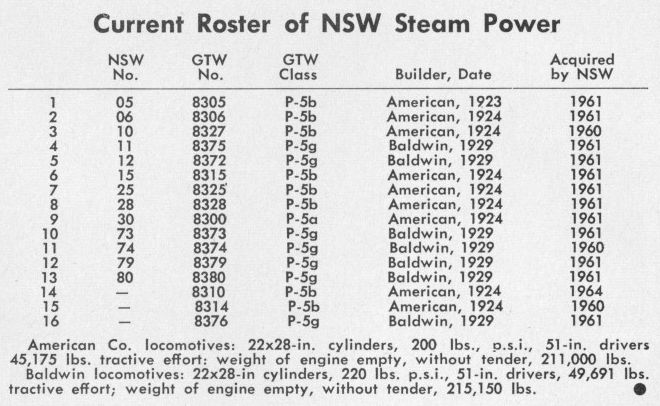

The 16 former Grand Trunk Western steamers that are now being used arrived in 1960 and 1961 when that road was on a steam-scrapping spree. They were intended to be dismantled along with hundreds of other steamers from the Nickel Plate, the GTW, and the Burlington. Someone wisely noticed what good shape these 0-8-0’s were in, compared to the smaller power then being operated and decided to save them, popping their own power into the ovens instead.

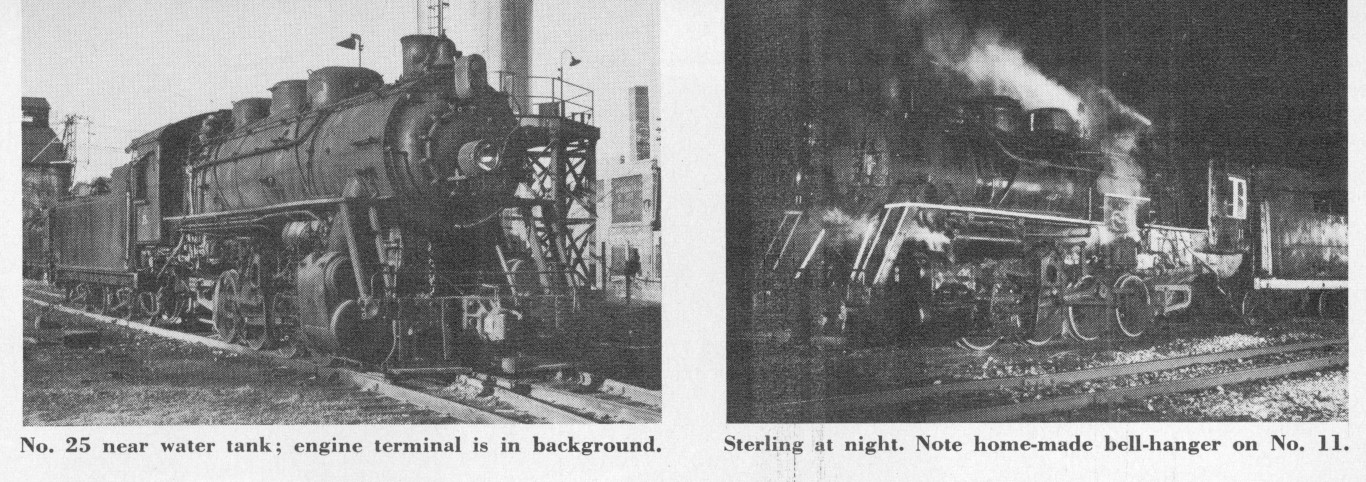

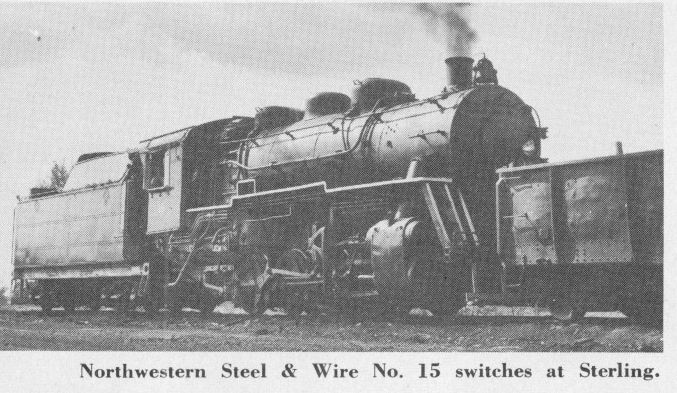

Today, the company has several miles of track lined with dangerous debris. The plant usually works two or three steamers through it for seven days a week, 24 hours a day. The locos haul scrap to furnaces and haul finished products to the shipping stations and weighing scales. The plant connects with the Chicago & North Western, and its steamers briefly venture out daily on their iron to pick up or drop off cars.

The company uses dozens of tenders off scrapped Burlington 4-8-4’s and 2-1O-4’s and GTW 2-8-2’s. The tenders have had their coal bunkers and water baffle plates removed. The cars are now big open-top shells, but still sport the heralds of their former owners. Since the tenders have couplers only at one end, they are cleverly connected in units of two, drawbar to draw bar. They can be separated for switching only at the ends with the knuckle couplers.

As late as 1962, Northwestern had more than 100 steamers from various roads laying, around, awaiting the cutting torches and smelters. On my first visit to Sterling in 1963, I found Burlington 2-1O-4’s and 4-8-4’s, Grand Trunk Western 2-8-0’s, 2-8-2’s, 4-6-2’s, 4-8-2’s, and 4-8-4’s, and even some NKP Berkshires awaiting the torch. Grand Trunk Western 4-8-4 No. 6322, of fantrip fame, was rusting away with “Farewell to Steam” still chalked on her rusted Vanderbilt tender. Nickel Plate Berkshire No. 730, which was often used in public relations and press release photos during the railroad’s steam-conscious 1940’s, stood beside the others, awaiting the same fate and a reprieve that never came.

For a while during the early sixties, NSW saved bells, headlights, whistles, number plates, and builder’s plates from the engines, selling the booty to trophy hungry fans who hated to see their favorite locomotives scrapped. Today, all such parts have long since been cleaned out, as well as the Burlington’s first 4-8-4, No. 5601, class 05a. In 1963 I sadly watched her being cut up. Today, only the GTW switchers remain, due to their usable wheel arrangement. Once a pair of 600-hp. EMD units were bought second-hand and tried out. They proved too frail, as diesels can’t work under these conditions. Finally they were taken off their trucks. Inventive Northwestern used the diesels as emergency power units behind the mill, and applied the traction motors and trucks to a roving gantry crane.

It’s hard work keeping, this railroad operating. Northwestern employs 24 trainmen, a track crew, and a maintenance crew to keep the miles of track, 16 steamers, and dozens of cars running. Daily the steamers consume up to 24 tons of coal and 48,000 gallons of water. Then, of course, the fires must be serviced for changes in crew.

A major problem affecting the NSW operation is the enormous amounts of sharp, twisted scrap metal lying about. Anyone could easily get hurt around all this junk. Because of it, engines and cars jump the track almost as a routine matter. In fact, I have seen cars being pulled about with 20-foot bands of bouncing, swinging steel slapping about the car sides, wrapped around the wheels, and lashing out at switch-stands or anything it passed. Since only the locomotive’s brakes are used (the car brakes are not working), stopping for an emergency is quite difficult, and sometimes the cars bang into the back of the tender or wrench a drawbar.

For these reasons, I understand the extreme insurance restrictions and the often hostile guards working for, the safety-conscious Northwestern. I was personally escorted out of town and over the bridge into Rock Falls the night I made the cover photo used on the current Railroad Magazine and the other night shot illustrating this article. The plant guards, wearing yellow safety helmets and steel-toed shoes, felt that I had overstayed my welcome and visitor’s rights by hanging around after dark and firing off several dozen flash bulbs. Perhaps I was lucky, however. Many fans have found out that in taking photos without a permit you run the risk of having your camera or film confiscated. A fan should show the courtesy and the small effort it takes to get such a pass, respecting the wishes of a company which is currently using 16 steam locomotives.

Recently, health-conscious citizens of Sterling have been up in arms about the smoke that NSW is adding to the atmosphere. As a result, the steamers appear to be scapegoats. Mr. Dillon wants his company to try and replace coal with natural gas, condensed into liquid form as fuel.

“Then the engineers could come to work in white shirts,” he says.

The engineers, incidentally, run the locomotives without firemen, doing their own firing while switching cars.

Last spring, the Railroad Club of Chicago had the first organized fan trip to Sterling to see the steamers, and found 0-8-0 No. 25 operating with an ex-Kansas City Southern Vanderbilt oil tender, coupled backward behind her! Evidently the company is trying oil as fuel for a while. Once chief mechanic Larry Cain experimented with diesel fuel oil in place of coal in a steamer.

“That didn’t work out,” he recalls. “For one thing, so much fuel was gulped up in the firebox that we were refilling the tank every half-hour.”

Once before in 1964, Northwestern fired up oilburners. It converted two Burlington 2-10-4’s to burn oil and placed them behind the mill, with rods off and a huge smokestack attached. The hulks supplied steam to the plant for a while. This operation has ended now, and the gallant Texas types were put to death in the mill which they had served. These were the last 2-10-4’s fired up in North America!

As of now, the steamers look as if they will be used for a few more years, but don’t count on it. I have seen overnight changes in management’s policy to do away with steam power on other all-steam roads. But as long as Mr. Dillon wants to hear the beloved sounds of steam locomotives echo through his steel mill, there will be smoke and steam over Sterling.